Is Feed Forawrd Better Than Feedback

Listen to my interview with Joe Hirsch (transcript):

Sponsored by Kiddom and Pear Deck

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What's the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

As teachers, we pretty much give feedback all day long. We tell students how they can improve on assignments, we praise them for things they're doing well, we correct their incorrect responses, and we redirect them when they behave in ways that aren't helpful to learning.

And that's just the students. We also give feedback to our colleagues, although in most cases, these exchanges don't happen as often or as freely as they probably should. We receive plenty of feedback as well, from our students, their parents, our administrators, and our peers. And we encourage our students to give feedback to each other, albeit with pretty uneven results. Really, the experience of school could be described as one long feedback session, where every day, people show up with the goal of improving, while other people tell them how to do it.

And it doesn't always go well. As we give and receive feedback, people get defensive. Feelings get hurt. Too often, the improvements we're going for don't happen, because the feedback isn't given in a way that the receiver can embrace.

It turns out there's a different way to give feedback that works a lot better, a way of flipping its focus from the past to the future. It's a concept called "feedforward," which was originally developed by a management expert named Marshall Goldsmith. As far as I can tell, not a lot of educators are familiar with the practice of feedforward, and I really think if we learned how to do it and started using it more consistently, it could make a huge difference in how our students grow and how we grow as professionals.

In this week's podcast, I interview Joe Hirsch, author ofThe Feedback Fix: Dump the Past, Embrace the Future, and Lead the Way to Change. (Bookshop.org | Amazon). In the book, Joe digs deep into the practice of feedforward and shows us how and why it works. You can listen to our full conversation in the player above, read the full transcript, or stay right here—I'll give you a quick overview.

What's Wrong with the Way We Give Feedback?

When we give feedback to our students, or when our co-workers or administrators give feedback to us, the focus is on the past. "People can't control what they can't change, and we can't change the past," says Hirsch. "And that happens to be the focus of most of the feedback that we give or receive."

More specifically, backward-looking feedback doesn't often get good results for three reasons:

- It shuts down our mental dashboards. "When we get negative feedback about something that we can't change or control," Hirsch says, "our brains flood with stress-inducing hormones, cortisol, that trigger our threat awareness and put us on the defensive. The parts that are responsible for executive function, for creativity, the parts that allow us to sort of set our agendas and make rational decisions, essentially we are in a state of mental paralysis."

- It focuses primarily on ratings, not on development. Most of feedback's time and energy is spent on looking back and rating (or grading) performance that's already over, rather than focusing on what can be done from now on. "When feedback consists of an impersonal set of performance standards, we're overlooking the essential goal of feedback, and that's to create positive and lasting improvement."

- It reinforces negative behaviors. "When we hear about flaws that we can't fix anymore—because they're in a past that we can't change—it creates a feeling of learned helplessness, the feeling that we are unable to do anything about our future. Instead of committing ourselves to improvement, which is what we would hope would happen, we hold onto this debilitating view of who we are instead of focusing on who we are becoming."

What is Feedforward?

When we give feedforward, instead of rating and judging a person's performance in the past, we focus on their development in the future.

Suppose my student is writing an essay. Instead of waiting until she is finished, then marking up all the errors and giving it a grade, I would read parts of the essay while she is writing it, point out things I'm noticing, and ask her questions to get her thinking about how she might improve it.

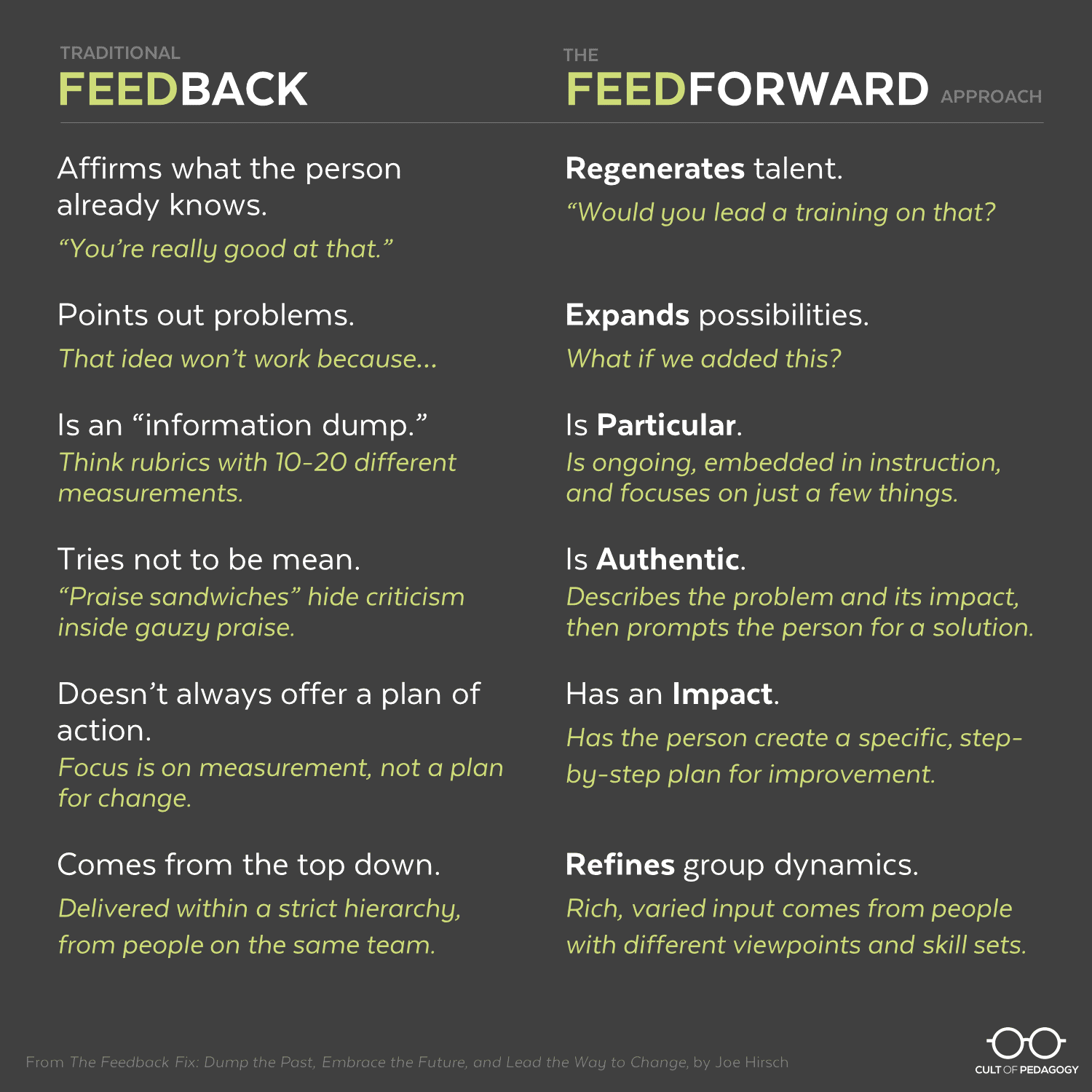

In his book, Hirsch takes this broad concept of feedforward and defines six components of it, six specific characteristics of feedforward that make it so effective. He refers to these by the acronym REPAIR (regenerates, expands, particular, authentic, impact, refines).

So let's take a look at each of these. If you want to implement feedforward well, it should have these attributes:

It REGENERATES talent.

The most effective kind of feedforward helps people see opportunities for growth—ways they could take on new opportunities and roles. "At the simplest level," Hirsch writes in his book, "it leads to the unmistakable feeling that we're moving forward in our professional and personal lives. Getting positive feedback about our performance may feel good, but it doesn't break new ground. It merely confirms what we already know about ourselves and our talents, essentially holding our growth in check. But when feedback gets us thinking about how to spread that talent to others, it has a multiplying effect."

So when we notice that a student is developing a strength or an interest in an area, instead of just pointing that out, we might give the student an opportunity to enter their work in some kind of competition, publish it in some way, or share it with others in a presentation, rather than simply keeping it to themselves. This helps students see themselves in a new light and gets them thinking about ways they could grow.

It EXPANDS possibilities.

Effective feedback starts with what is and helps add to it, expanding what's possible, rather than simply pointing out problems. In his book, Hirsch describes a concept used by Pixar studios called "plussing." When Pixar's creators get together to review a day's work, they are expected to give each other feedback to improve the work. What makes these sessions so effective is one important rule: Participants can't point out a problem without proposing an alternative, saying "What if?" to a problem.

This concept of "plussing" could work wonders in staff or committee meetings: When we are discussing possible solutions to an issue, rather than shooting down ideas that might not work, we could add to them by making small tweaks. "That's an interesting idea. What if we made this small change and tried that?" This technique would also work beautifully with project-based learning tasks, when students may need to come up with several ideas for solving a problem before arriving at the best solution.

It is PARTICULAR.

Far too often, feedback is given in an "information dump," with lots of criteria being measured and reported on at the same time. This can be a pretty ineffective way to help people grow. "There's a limit to how much we can absorb and operationalize in any given time," Hirsch says. "Feedforward is really about picking your battlegrounds strategically and selectively." He advises us to make feedback an ongoing process that is embedded in the day-to-day work, and to only focus on a few things at a time.

So rather than wait until an assignment is done to point out all the ways a student can improve, find ways to give them specific pointers while they work, and only one thing at a time, so students can process and act on it right away.

It is AUTHENTIC.

No one particularly likes giving criticism. "We see problems, we see pitfalls in other people, and we know it's a problem," Hirsch says, "but we don't want to be mean, right? We don't want to crush them. So the tendency is to either avoid giving feedback altogether or to disguise it as a praise sandwich, where we basically slip one piece of criticism in between two very, very surface level gauzy praises."

The problem with that approach, Hirsch explains, is what's called the recency effect: People remember most the thing they heard last. So when you tack on some praise after delivering constructive feedback, the person doesn't really absorb the critical part as well as they would if you'd just given it to them more directly.

Hirsch recommends a more direct approach: Describe what's happening, explain why it's a problem, then prompt the person for a solution. "When delivered this way," Hirsch explains, "it puts people at ease, it takes them off the defensive. It is clear, it is concise, it's locating the problem, it's looking for solutions together. People don't want a praise sandwich. People want the truth."

This approach could work with academic situations or classroom management problems: If you're dealing with a student who is disrupting class, describe the behavior you're seeing, explain why it's a problem, then ask the student for ideas on how to solve it. It sounds really simple, but if what you're doing right now isn't giving you the results you want, it's worth a try.

It has IMPACT.

One of the reasons people don't make progress after receiving feedback is that they don't necessarily know what to do with it. "If you want feedback to make an impact," Hirsch notes, "you have to put it in terms that people can operationalize." In his book, he cites studies showing that regular feedback doesn't typically result in a transfer of new skills or habits, but when that feedback is combined with coaching, the transfer skyrockets to 95 percent.

So if a student regularly forgets to bring materials to class, rather than simply telling him to change, help him make a specific plan for improvement. Ideally, that plan should have lots of small steps to make it achievable, and the student should take the lead in developing that plan.

It REFINES group dynamics.

"Feedback is a team sport," Hirsch says. "It is not just something that happens one to one. It happens in groups and across and within organizations. And when we dump that command and control nature of traditional feedback, we make room for something much more collaborative and shared."

So rather than give feedback in a top-down, hierarchical model, open up more pathways for people to get feedback from their peers, even those whose jobs might on the surface have little in common with our own. In his book, Hirsch borrows a term from management circles known as "creative abrasion," which is what happens when people with opposing views work on the same task together. Although it can result in more conflict, the contributions from different points of view usually produce a higher-quality product in the end.

This idea can play out in a lot of educational settings: Instead of just having our department head observe our teaching, why not get feedback from someone who teaches a completely different subject? When students go to the same peers for feedback on their work, have them seek out the opinion of someone new, or consider getting the input of a group of students from a different class or grade level entirely.

There's nothing simple or straightforward about telling people how to improve. So it's no surprise that we're still figuring it out and finding new ways to refine it. If the feedback you're giving to your students, your coworkers, and even the people at home isn't having quite the effect you intend, try shifting to a feedforward approach. Doing so can help us, as Hirsch says, stop seeing ourselves just as who we are, but who we are becoming. ♦

Learn more about Joe Hirsch on his website or visit his LinkedIn page. Teachers who read The Feedback Fix should also grab this free Discussion Guide for Teachers to help apply the book's principles to your own work.

Come back for more.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You'll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Source: https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/feedforward/

0 Response to "Is Feed Forawrd Better Than Feedback"

Post a Comment